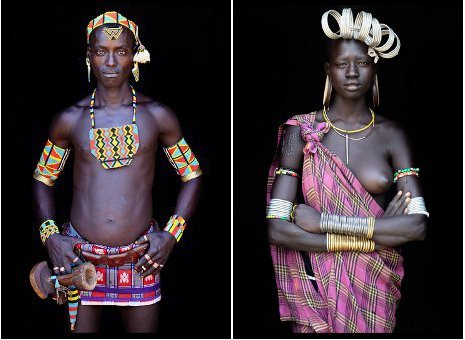

Sub-Saharan Africa has been a natural laboratory for the evolution of sexually transmitted pathogens,

including strains that can manipulate their hosts.

Are we being manipulated by microbes? The idea is not so whacky. We know that a wide range of microscopic parasites have evolved the ability to manipulate their hosts, even to the point of making the host behave in strange ways. A well-known example is Toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan whose life cycle begins inside a cat. After being excreted in the cat's feces, it is picked up by a mouse and enters the new host's brain, where it neutralizes the fear response to the smell of cat urine. The mouse lets itself be eaten by a cat, and the protozoan returns to a cat's gut—the only place where it can reproduce (Flegr, 2013).

T. gondii can also infect us and alter our behavior. Infected individuals have longer reaction times, higher testosterone levels, and a greater risk of developing severe forms of schizophrenia (Flegr, 2013). But there is no reason to believe that T. gondii is the only such parasite we need to worry about. We study it in humans simply because we already know what it does in a non-human species.

Researchers are starting to look at manipulation by another human parasite, a sexually transmitted bacterium called Chlamydia trachomatis. Zhong et al. (2011) have found that it synthesizes proteins that manipulate the signalling pathways of its human host. These proteins seem to facilitate reinfection, although there may be other effects:

Despite the significant progresses made in the past decade, the precise mechanisms on what and how chlamydia-secreted proteins interact with host cells remain largely unknown, and will therefore still represent major research directions of the chlamydial field in the foreseeable future. (Zhong et al., 2011)

What else would a sexually transmitted pathogen do to its host? For one thing, it could cause infertility:

While several nonsexually transmitted infections can also cause infertility (e.g., schistosomiasis, tuberculosis, leprosy), these infections are typically associated with high overall virulence. In contrast, STIs tend to cause little mortality and morbidity; thus, the effect on fertility seems to be more "targeted" and specific. In addition, several STI pathogens are also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and infant mortality (Apari et al., 2014)

Chlamydia is a major cause of infertility, and this effect seems to be no accident. Its outer membrane contains a heat shock protein that induces cell death (apoptosis) in placenta cells that are vital for normal fetal development. The same protein exists in other bacteria but is located within the cytoplasm, where it can less easily affect the host's tissues. Furthermore, via this protein, Chlamydia triggers an autoimmune response that can damage the fallopian tubes and induce abortion. This response is not triggered by the common bacterium Escherichia coli. Finally, Chlamydia selectively up-regulates the expression of this protein while down-regulating the expression of most other proteins (Apari et al., 2014).

But how would infertility benefit Chlamydia and other sexually transmitted pathogens? Apari et al. (2011) argue that infertility causes the host and her partner to break up and seek new partners, thus multiplying the opportunities for the pathogen to spread to other hosts. A barren woman may pair up with a succession of partners in a desperate attempt to prove her fertility and, eventually, turn to prostitution as a means to support herself (Caldwell et al., 1989). This is not a minor phenomenon. STI-induced infertility has exceeded 40% in parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Apari et al., 2011).

It gets kinkier and kinkier

Does the manipulation stop there? We know, for instance, that sexual promiscuity correlates with the risk of contracting different STIs, but is this a simple relationship of cause and effect? Could an STI actually promote infidelity by stimulating sexual fantasizing about people other than one's current partner?

Let's look at another pathogen, Candida albicans, commonly known as vaginal yeast, which can cause an itchy rash called vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). Reed et al. (2003) found no significant association between VVC and the woman's frequency of vaginal sex, lifetime number of partners, or duration of current relationship. Nor was there any association with presence of C. albicans in her male partner. But there were significant associations with the woman masturbating or practicing cunnilingus in the past month.

VVC is thus more strongly associated with increased sexual fantasizing, as indicated by masturbation rate, than with a higher frequency of vaginal intercourse. This does look like host manipulation, although one might wonder why it doesn't translate into more sex with other men, this being presumably what the pathogen wants. Perhaps the development of masturbation as a lifestyle (through use of vibrators and pornography) is making this outcome harder to achieve.

A sexually transmitted pathogen can also increase its chances of transmission by disrupting mate guarding. This is the tendency of one mate, usually the male, to keep watch over the other mate. If mate guarding can be disabled or, better yet, reversed, the pathogen can spread more easily to other hosts. This kind of host manipulation has been shown in a non-human species (Mormann, 2010).

Do we see reversal of mate guarding in humans? Yes, it's called cuckold envy—the desire to see another man have sex with your wife—and it's become a common fetish. Yet it seems relatively recent. Greco-Roman texts don't mention it, despite abundant references to other forms of alternate sexual behavior, e.g., pedophilia, cunnilingus, fellatio, bestiality, etc. The earliest mentions appear in 17th century England (Kuchar, 2011, pp. 18-19). This was when England was opening up to world trade and, in particular, to the West African slave trade.

Sub-Saharan Africa has been especially conducive to sexually transmitted pathogens evolving a capacity for host manipulation. Polygyny rates are high, in the range of 20 to 40% of all adult males, and the polygynous male is typically an older man who cannot sexually satisfy all of his wives. There is thus an inevitable tendency toward multi-partner sex by both men and women, which sexually transmitted pathogens can exploit ... and manipulate.

What about sexual orientation?

A pathogen can also become more transmissible by giving its host a new sexual orientation. This strategy would disrupt the existing pair bond while opening up modes of transmission that may be more efficient than the penis/vagina one. Some vaginal strains of Candida albicans have adapted to oral sex by becoming better at adhering to saliva-coated surfaces (Schmid et al., 1995). Certain species that cause bacterial vaginosis, notably Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella, seem to specialize in female-female transmission (Muzny et al., 2013; Sobel, 2012).

Finally, there is the hypothesis that exclusive male homosexuality has a microbial origin (Cochran et al., 2000). Its main shortcomings are that (a) there is no candidate pathogen and that (b) exclusive male homosexuality has been observed in social environments with limited opportunities for pathogen transmission, such as small bands of hunter-gatherers across pre-Columbian North America (Callender & Kochems, 1983). On the other hand, there seems to have been a relatively recent shift in European societies from facultative to exclusive male homosexuality, so something may have happened in the environment, perhaps the introduction of a new pathogen (Frost, 2009).

Both male and female homosexuality seem to have multiple causes, but it’s likely that various pathogens have exploited this means of spreading to other hosts.

Conclusion

This is a fun subject when it concerns silly mice or zombie ants. But now it concerns us. And that's not so funny. Can microbes really develop such demonic abilities to change our private thoughts and feelings?

It does seem hard to believe. Perhaps this is an argument for intelligent design. After all, only an all-knowing designer could have made creatures that are so small and yet capable of so much ... things like inducing abortion, breaking up marriages, and altering normal sexual desires. Yes, such an argument could be made.

But I don't think anyone will bother.

References

Apari, P., J. Dinis de Sousa, and V. Muller. (2014). Why Sexually Transmitted Infections Tend to Cause Infertility: An Evolutionary Hypothesis. PLoS Pathog 10(8): e1004111.

http://www.plospathogens.org/article/in ... at.1004111

Caldwell, J.C., P. Caldwell, and P. Quiggin. (1989). The social context of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, Population and Development Review, 15, 185-234.

https://www.soc.umn.edu/~meierann/Teach ... ldwell.pdf

Callender, C. and L.M. Kochems. (1983). The North American Berdache, Current Anthropology, 24, 443-470.

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/2 ... 4311299061

Cochran, G.M., P.W. Ewald, and K.D. Cochran. (2000). Infection causation of disease: an evolutionary perspective, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 43, 406-448.

http://www.isteve.com/infectious_causat ... isease.pdf

Flegr, J. (2013). Influence of latent Toxoplasma infection on human personality, physiology and morphology: pros and cons of the Toxoplasma-human model in studying the manipulation hypothesis, The Journal of Experimental Biology, 216, 127-133. http://jeb.biologists.org/content/216/1/127.full

Frost, P. (2009). Has male homosexuality changed over time, Evo and Proud, March 5

http://evoandproud.blogspot.ca/2009/03/ ... -over.html

Kuchar, G. (2001). Rhetoric, Anxiety, and the Pleasures of Cuckoldry in the Drama of Ben Jonson and Thomas Middleton, Journal of Narrative Theory, 31 (1), Winter, pp. 1-30.

Mormann, K. (2010). Factors influencing parasite-related suppression of mating behavior in the isopod Caecidotea intermedius, Theses and Disserations, paper 48

http://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/48

Muzny, C.A., I.R. Sunesara, R. Kumar, L.A. Mena, M.E. Griswold, et al. (2013). Correction: Characterization of the vaginal microbiota among sexual risk behavior groups of women with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS ONE 8(12):

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Ad ... ne.0080254

Reed, B.D., P. Zazove, C.L. Pierson, D.W. Gorenflo, and J. Horrocks. (2003). Candida transmission and sexual behaviors as risks for a repeat episode of Candida vulvovaginitis, Journal of Women's Health, 12, 979-989.

http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10 ... 3322643901

Schmid, J., P.R. Hunter, G.C. White, A.K. Nand, and R.D. Cannon. (1995). Physiological traits associated with success of Candida albicans strains as commensal colonizers and pathogens, Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 33, 2920-2926.

http://jcm.asm.org/content/33/11/2920.short

Sobel, J.D. (2012). Bacterial vaginosis, Wolters Kluwer, UpToDate

http://www.uptodate.com/contents/bacterial-vaginosis

Zhong, G., L. Lei, S. Gong, C. Lu, M. Qi, and D. Chen. (2011). Chlamydia-Secreted Proteins in Chlamydial Interactions with Host Cells, Current Chemical Biology, 5, 29-37

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/b ... 1/art00004